I Walked to the Gallows With the Nazi Chiefs

By Chaplain Henry F. Gerecke

As told to Merle Sinclair

[as it appeared in The Saturday Evening Post, September 1, 1951*]

It was the duty of the Chaplain of Nuremberg Prison to offer Christian comfort to Hitler’s gang. Now, after five years under a bond of silence, he tells how they repented before the hangman’s trap fell.

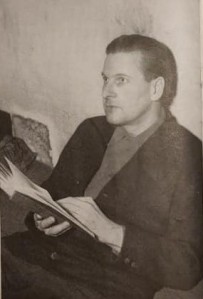

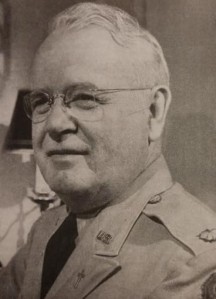

“Chaplain Gerecke. The Nazi prisoners wrote to his wife, asking her to urge him to stay in Nuremberg” (photo by Ralph Boyle).

It is five years since I served my stretch in Nuremberg prison–as chief chaplain during the trials of the Nazi leaders by the International Military Tribunal and spiritual adviser to the fifteen Protestant defendants. My assistant, Catholic Chaplain Sixtus O’Conner, and I spent eleven months with the perpetrators of World War II. We were the last to counsel with these men, and made ten trips to the execution chamber. The world has never heard our story.

When, some years ago, I asked the United States Army for the necessary permission to share this experience with my fellow Americans, I was asked to wait. I believe the public’s reaction to the trials was responsible. Consequently, my reminiscences have been confined to two reports, both written previously and read only by fellow chaplains and certain young fold of my Lutheran faith.

However, I believe that the story, told now, will help to stress the lessons we should have learned from the careers and downfall of Hitler’s elect, at a time when we need such lessons worse than ever.

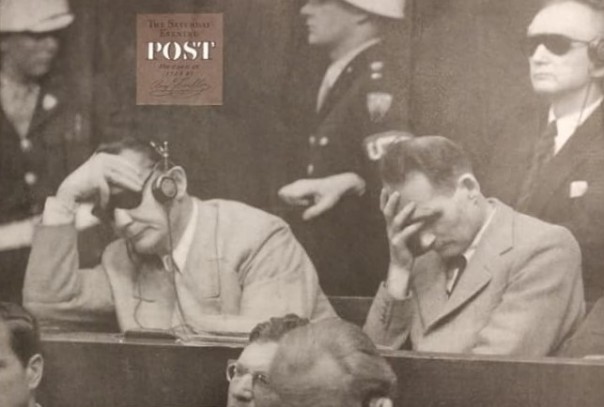

“Hermann Goering and Rudolph Hess at the Nuremberg Trials. Hess, one-time Deputy Fuhrer, refused religious counsel while he was waiting for trial.”

Our fallacy regarding the Nazis has been that they were “a breed apart”; that they could not happen here, and that, having disposed of them, we could breathe freely. Now the democracies are regarding apprehensively the nearly 400,000 votes given a swastika-patterned party in Saxony recently. They are pondering the international movement organized in Sweden by thirty fascist leaders from eight countries, similarly minded groups formed in South American cities, and the 100,000 to 200,000 active supporters of Nazi doctrine in Austria.

The findings of the prison psychologists bear out my conviction that the defendants at Nuremberg were basically the same as other mortals Leaders such as they, are the likely product of any culture based on materialism, corruption and gross prejudices. And given a master rabble rouse with the cunning and guile of the late Huey Long to capitalize on those same weaknesses in our own country, such gangster rules could happen here. Then our last bulwark against communism–the moral and spiritual integrity which is the cornerstone of our freedom–would be shattered.

I particularly want to emphasize that, when stripped of all they had held important, and when offered the eternal verities, most of the twenty-one defendants were able to come to their moral senses and repent.

This is what happened in Nuremberg prison: More than half of the Nazis there, before going to the gallows or their long imprisonment at Spandau, asked God for forgiveness of their sins against Him and humanity and returned to the Christian faiths of their forebears!

They did so in a spirit that convinced me that their repentance was genuine. I have had many years of experience as a prison chaplain and do not believe I am easily deluded by phony reformations at the eleventh hour.

Though attendance was voluntary, thirteen of the Protestants came regularly and co-operatively to chapel services. Only Rudolf Hess and Alfred Rosenberg refused to do so. Two of the six reared as Catholics, Ernst Kaltenbrunner and Hans Frank, returned to their church with Chaplain O’Connor’s help.

Two others, Franz von Papen and Artur Seyss-Inquart, did not consider that they had left it. These four always attended Catholic services. Only Alfred Jodl and Julius Streicher refused all spiritual counsel. However, with Hess and Rosenberg, they professed belief in God.

Seven of the defendants, at their own request and after long self-examination under my guidance, partook of communion according to the rites of the Lutheran Church: Wilhelm Keitel, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Fritz Sauckel, Erich Raeder, Albert Speer, Hans Fritzsche and Baldur von Schirach. And I am very slow about administering the Lord’s Supper. I must feel convinced that each candidate not only understands its significance but that, in penitence and faith, he is ready for this sacrament.

No defendant was ever ordered by the military to let the chaplain see him. Chaplain O’Connor and I usually asked the prisoners if they cared to be called on Frequently, we would find notes from them in our office, asking for visits.

Many persons, I find, are not even aware that chaplains were provided the Nazi prisoners. The Geneva Conventions specify that our services be made available to all prisoners of war. However, the German offices were relieved of military rank prior to trial and were treated as persons without official status. In the opinion of Maj. Gen. Roy H. Parker, chief of chaplains, spiritual counsel was bestowed–through the good graces of the United States Army–in keeping with the fundamental law recognized in America as granting the benefits of religion to all. This provision made a deep impression on the defendants. I am glad now to express the gratitude some of them asked me to convey to the American people.

The Chaplain Makes His Big Decision

I was in Munich with the 98th General Hospital when Col. James Sullivan, commanding, told me an order was going through for my transfer to Nuremberg. However, he explained, I might take advantage of my eligibility to return to the inactive reserves if I preferred. I was badly shaken. I almost went home. How could a humble preacher, a one-time Missouri farm boy, make any impression on disciples of Adolf Hitler? How could I approach them? How would they treat me? How could I summon the true Christian spirit which this mission demanded of a chaplain?

I had plenty of excuses for bitterness toward them. I had been at Dachau concentration camp where my hand, touching a wall, had been smeared with the human blood seeping through. In England, for fifteen months, I had ministered to the wounded and dying from the front lines. My oldest son had been literally ripped apart in the fighting. The second suffered severely in the Battle of the Bulge. My third would soon enter the Army.

The next few days, I prayed harder than I ever had in my life. Slowly, the men at Nuremberg became to me just lost souls, whom I was being asked to help. If, as never before, I could hate the sin, but love the sinner—-

“I’ll go,” I told Colonel Sullivan.

I had been chosen because I spoke German; I was Lutheran; I had spent more time in jail than any other preacher the Army had handy. I had been director of prison work for the St. Louis City Mission for many years.

In November, 1945, I was assigned to the 6850th Internal Security Detachment, which had charge of the prisoners and the mechanics of the trials. Col. B. C. Andrus was prison commandant. Chaplain O’Connor, from New York City, was established at the prison when I arrived. He and Chaplain Carl Eggers, who had been serving temporarily in the Protestant capacity, gave me all the background they could.

Chaplain O’Connor spoke German well. He was in his early forties, earnest, diligent and delightful to work with. I hope our paths cross again soon. As we grew better acquainted, we developed a grim little joke between us. “At least,” he would say, “we Catholics are responsible for only six of these criminals. You Lutherans have fifteen chalked up against you.” But most of the time we certainly didn’t feel like joking.

The prison block was three-storied. The ground floor, where the defendants were confined, had a broad corridor running its length, with cells on either side and circular stairs at each end leading to the upper cell rows. Each cell door had a type of Judas window in it as shoulder height, which opened down, forming a shelf where meals were placed. It was kept open at all times, for observation. A guard stood at each cell the clock around. He could not speak to the prisoner except in stern correction of a breach of discipline. The waiters who brought the food were not permitted even to answer a greeting.

Chaplain Eggers took me first to the cell of Rudolf Hess. I was terribly frightened. How could I say the right thing–and say it in German besides? Because Hess spoke English, the chaplain used it to introduce me. “This is Chaplain Gerecke, who will be on duty here from now on. He will conduct services and be available for counsel if you wish to have him.”

I offered my hand, and Hess put out his. Just then Chaplain Eggers was called away, and I was on my own.

“Would you care to attend chapel service Sunday evening?” I asked in German.

“No,” he replied–in English.

Then in English, I asked him, “Do you feel you can get along as well without attending as if you did?”

“I expect to be extremely busy preparing my defense,” he answered. “If I have any praying to do, I’ll do it here.”

When I left him, I knew I had accomplished nothing. Chaplain Eggers did not return. I had my own introductions to make if I wanted to get on with my visits.

“Hitler’s Reichsmarshal, Hermann Goerring, attended religious services regularly while in Nuremberg, but he told the prison psychiatrist that he went to chapel just to get out of his cell.”

I stopped next at the cell of Hermann Goering. I dreaded meeting the big, flamboyant egotist worse than any of the others. Through the small aperture I had a chance to size him up for a moment. He was reading a book and smoking his meerschaum pipe. As I entered, he jumped up and clicked his heels. I greeted him in German, and he bowed. Then he said, “Will you come in and spend some time with me?”

We shook hands and he offered me his only chair. “I heard you were coming and I am glad to see you,” he said.

All my diffidence dissolved in his shrewdly calculated amiability. He was a very rapid talker. He asked about my family and promised to be at chapel. Then he asked if Hess had agreed to come. When I said no, he said he would speak to him about the matter! Later that day, he and Hess were conducted to the exercise yard for the same quarter hour. Though they were forbidden to communicate, I distinctly overheard Goering get across to Hess that it would doubtless be in their favor to appear at chapel.

“I wouldn’t give it a thought,” Hess retorted. The next time I saw Goering, he apologized for his failure to persuade his colleague. A wily fellow, Hermann Goering.

I have been criticized for offering my hand to these men. Don’t think it was easy for me. But I knew I could never win any of them to my way of thinking unless they liked me first. Furthermore, I was there as the representative of an all-loving Father. The gesture did not mean that I made light of their malefactions. They soon found that out.

Former Field Marshal Keitel, Hitler’s pet general, was also deep in a book when I entered. He welcomed me heartily. I asked what he was reading. He all but knocked me speechless by replying, “My Bible.” Now, nobody had told me a thing to suggest that I would find any prisoner reading Scripture! Keitel said he had carried his Bible through both World Wars and in between, and added, “I know from this book that God can love a sinner like me.”

A phony, I thought. But the longer I listened, the more I felt he might be sincere. He said he had not been a good Christian. He insisted he was very glad that a nation which would probably put him to death thought enough of his eternal welfare to provide him with spiritual guidance. He would be at chapel, he added.

After a bit he said, “I was just getting ready for my daily devotions. Would you care to join me?”

This I wanted to see!

He knelt beside his cot and read a portion of Scripture. Then he folded his hands, looked heavenward and began to pray. Never have I heard a prayer quite like that one. Though I cannot break confessional confidence to share it, I can say that he spoke penitently of his many sins and pleaded for mercy by reason of Christ’s sacrifice for him. When he finished, we repeated the Lord’s Prayer together, and I spoke a benediction.

After I had greeted Fritz Sauckel, Hitler’s labor chief, he put his hands on my arms and said with great feeling, “As a clergyman, you are one person to whom I can open my heart. ” During our conversation he would wipe away tears and speak earnestly of his faithful wife and eleven children, one of whom had been killed in the war. He asked what arrangments could be made for serving communion to prisoners desiring it.

As I progressed with my visits, these defendants–some eagerly, others with cool courtesy–also told me they would attend services: Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hans Fritzsche, Wilhelm Frick, Hjalmar Schacht, Baldur von Schirach, Baron von Schirach, Baron von Neurath, Albert Speer, Walter Funk and Erich Raeder.

Admiral Raeder asked me to be sure to see his friend, Admiral Doenitz. When I did, Doenitz said, “If you have the courage to come here, I’ll attend your services. I think you’ll probably help me.”

Alfred Rosenberg, chief Nazi philosopher, remained the sophisticate. He had no use for his childhood faith. He told me politely that he felt no need of my help. He said I would be welcome if I cared to visit–but perhaps I had better spend the time with his colleagues. My visits to the six prisoners in Chaplain O’Conner’s charge were, of course, merely “social,” as were his calls on the Protestants.

Since the regular chapel had been designated for the use of the several hundred witnesses confined to the prison, we conducted services for the defendants in a tiny, improvised chapel composed of two cells with the wall knocked out. The only equipment was a small altar, an organ, chairs, two candlesticks, a crucifix and hymnbooks. A former lieutenant colonel of the SS Polizei was the organist. Toward the end of the trials, he made me happy by renewing his vows with the Lutheran Church.

Protestant services included hymns, Scripture reading, prayers, sermon and benediction. The thirteen who attended always behaved in a devotional manner. Hermann Goering told Dr. G. M. Gilbert, the prison psychologist, that he went to chapel just to get out of his cell. But he knew how to behave.

In the Lutheran Church, a Bible verse is dedicated to each child by the pastor at confirmation time. Every one of my thirteen had remembered his verse. My first communicant was Fritz Sauckel, at his request, after I had worked with him for several weeks. During my visits, we had read the Bible and had brief prayers, for which we usually knelt beside his cot. That was the way he wanted it. He said he had not worked with the Nazi Party with any idea of committing wrong against God or man As a former seaman and laborer, he insisted, he was working toward the ideal social community of which he had dreamed.

Before long, Hans Fritzsche, Baldur von Schirach and Albert Speer asked to review the catechism regarding the Lord’s Supper. I guided them in the Scriptures as best I could. They said, “We have surely forgotten so much of this.”

Fritzsche, a soft-spoken man for all his having been Hitler’s radio propagandist, gave me a wholehearted welcome the first day. He said he was deeply ashamed of having turned against the church and hoped to come all the way back to Christ.

Albert Speer, the Nazi production genius, was always the delightful conversationalist–and did not overplay the role the way Goering did. He spoke out right and left to his colleagues for the chapel worship. Frankly admitting the guilt of the Nazi regime, he told me he felt that the neglect of genuine Christianity caused its downfall.

I had many talks with von Schirach, Hitler Youth leader and youngest of the defendants. He would greet me with a boyish smile and perfect English and urge me to come often. His mother was American-born, from Philadelphia. He had been confirmed at the age of fourteen, but soon afterward became interested in the Nazi youth movement. He became a leader in it before he was twenty. Now he realized, he said, that every energy should have been used to develop loyalty to really Christian principles.

On the witness stand he called Hitler the mass murderer of all history, Goering could have choked him for saying it. Von Schirach was one of several prisoners who refused their evening meal after viewing the atrocity films in the courtroom.

After these three defendants–Fritzsche, Speer and von Schirach–had studied with me for several weeks, they asked for communion. A service was accordingly held in the tiny chapel. I shall never forget the sight of those three big men kneeling before the crucifix, asking that their sins be forgiven. So convincing was their bearing that the guards said to me, “Chaplain, you’ll not need us. This is holy business.” And they walked out!

Some will say of these men, “They were just scared into reforming.” My only answer is that I have been a preacher for a long time and have decided that that is the only way a good many folk find themselves. ONe of many proofs that the prisoners were not–with the exception of Goering–putting on an act was a news story out of Spandau some time ago which said that all the high Nazi prisoners there except Hess attended chapel regularly.

When Wilhelm Keitel received communion the first time, on his knees and under deep emotional stress, he told me, “You have helped me more than you know. May Christ stand by me all the way. I shall need Him so much.”

I had placed Erich Raeder, an ardent Bible student, as an intellectual skeptic because he had said at first that he could not accept certain Christian tenets. He seemed to be digging for justification of his doubts. But quite the opposite had taken place, he said now, and he was deeply interested in learning more. He would read the Scripture for the coming Sunday’s sermon and have questions ready when I visited him. After many queries regarding communion, he came one day to chapel with von Schirach to partake.

One of my most heartening experiences was observing the slow but steady progress of Joachim von Ribbentrop, the diplomat, from cool indifference to a truly sincere Christian faith. He had remarked, on my first visit, “This business of religion probably isn’t so serious as you consider it” He said his wife had led him away from the church. She certainly made it as difficult for me as she could through her letters–she wrote that she would offset my influence on her husband in every way she could. Bur von Ribbentrop began asking questions. The one that seemed to trouble him most was, “Can a man be patriotic and Christian at the same time?” After several months, he started reading the Bible and the catechism. He became more and more penitent, eager to turn from the past.

Christmas seemed to give impetus to some of the prisoners’ progress. On Christmas Eve, the silence in the big prison was so profound that it hurt. All thirteen of my “congregation” were glad, I think, to come to chapel. The organist opened the service by playing carols. I read the Christmas story from the Gospel according to Saint Luke and preached a short sermon.

Then Fritz Sauckel spoke up, “We never took time to appreciate Christmas in its Biblical meaning. Tonight we are stripped of all material gifts and away from our people. But we have the Christmas story. And that’s all we really need, isn’t it?”

The organist played again and glided softly into Stille Nacht. The men began humming, and a few sang. After the benediction we sat in silence for at least five minutes. On the way out, I wished each man the peace of Christmas. Even the guards seemed a little less grim.

Admiral Doentiz at first had insisted that I could hardly preach the Gospel without bringing in politics. I assured him that I knew little about his politics, and, since he would not be interested in mine, we would simply deal with the Word of God in relations to the hearts of men. He agreed. He said he had heard that I was from Missouri and, twisting our time-honored expression a bit, wondered whether I would be able to “show” him what I was talking about. He felt he needed chapel and co-operated fully.

Baron von Neurath had been slow in responding to my overtures about coming to services. He said he had never attended church regularly, but finally agreed that that was where he belonged. As we went along, he manifested genuine interest. His family was very gratified at his religious progress and wrote me often about his “getting right with God.”

In the spring of 1946, the defendants heard a rumor that the older officers of the United States personnel would soon be allowed to return home, if they chose to do so. That would include Chaplain Gerecke, they reasoned–I was fifty-four at the time. When they had moaned over separation from their families, I had done a little mild griping of my own. I probably mentioned my wife’s health, and the fact that I had not seen her for two and one-half years. At any rate, apparently, they decided that Mrs. Gerecke would be the chief influence for my return home.

Consequently, my wife, back in Missouri, one day received what someone termed the most incredible letter over sorted by St. Louis postal clerks. It was written in almost illegible German script. But accompanying it was an English translation, which read in part:

Your husband has been taking religious care of the undersigned…for more than half a year. We have now heard…that you wish to see him back home after his absence of several years. Because we also have wives and children, we understand this wish of yours very well.

Nevertheless, we are asking you to put off your wish to gather your family around you….Please consider that we cannot miss your husband now….It is impossible for any other to break through the walls that have been built up around us; in a spiritual sense even stronger than a material one….We shall be deeply indebted to you.

We send our best wishes to you and your family. God be with you.

The letter, sent through the regular prison censorship, had been signed by all twenty-one defendants. Hitler’s strong boys, who had scourged Christianity and broken the Ten Commandments more than any scoundrels in history, were beseeching an American housewife for the spiritual counsel of a pastor of the Lutheran Church, Missouri Synod!

So I stayed on at Nuremberg. Mrs. Gerecke told me to–airmail, special delivery. Chaplain O’Connor and I were very busy. The defendants were in court from ten until five o’clock, Monday through Friday. During that time it was our responsibility to visit as many of the witnesses as we could. We attended some portion of the court proceedings practically every day, in order to be informed in dealing with the prisoners.

We grieved at our failures with the men, rejoiced at each slight indication of spiritual awakening. I was never very sure of Wilhelm Frick, Hitler’s minister of the interior. He did not make any outright confession. It was not till the night he went to the gallows that he assured me he had found his Savior while attending our services.

Hjalmar Schacht, Reichsbank president, was very bitter about spending time in prison with men like Goering, who had once jailed him. He refused communion because, he said, his bitterness made him spiritually unprepared for it. “If this trial is fair, I’ll be freed,” he declared, “and then I should like to go to church with my wife and take the Lord’s Supper.” when he was pronounced not guilty, I remembered what he had said.

When the trials ended, the eight judges went into secret session for several weeks. During this period, Chaplain O’Connor and I agreed that we should petition the court to permit the prisoners’ families to visit them. We asked Justice Lawrence, president of the tribunal, if arrangements could be made. He replied, “Have them come before the verdict.”

Colonel Andrus notified all the wives and children. Upon their arrival in Nuremberg, they were quartered in homes under the direction of the Internal Security. The wives of Erich Raeder and Wilhelm Keitel were the only ones not to appear. Frau Keitel did not come because her husband had asked her not to–he felt he would go to pieces. Reader’s wife was a prisoner of the Russian secret police. The International Military Tribunal had ordered her release for the visit, and I went to the airport seven times to meet her, but the Russians never complied or explained.

Each prisoner was heavily guarded while he talked with his kin. They were not allowed to touch each other. In fact, a screen between them ruled out any chance of an object being passed through. Chaplain O’Connor or I, and an officer, always were present on the visitors’ side.

For the most part, these wives and children were unassuming. I remember Frau Sauckel, mother of those eleven children, as simple and kind. I decided that several of the mothers were Christian. Some of the children knew the same bedtime prayers I had learned as a child. We sometimes kept the youngsters in our office, while their parents visited, and talked to them a good deal. When the Schacht children, aged three and five, were there, we really had our hands full. They were the Katzenjammer Kids in action, thinking up all sorts of deviltry to disturb the somber prison atmosphere.

Emmy Goering was a woman of considerable grace and charm. With tears in her eyes, she urged her daughter Edda to talk to me. I asked the little girl if she said her prayers.

She replied, “I pray every night.”

“And how do you pray?” I inquired.

“I kneel by my bed and look up to heaven and ask God to open my daddy’s heart and let Jesus in.”

When I tried to talk in a similar vein with Alfred Rosenberg’s daughter, a pretty thirteen-year-old, she interrupted, “Don’t give me any of that prayer stuff.”

I asked “Is there anything at all I can do for you?”

“Yes,” she answered, “Got a cigarette?”

Perhaps uncharitably, I labeled Frau von Ribbentrop the most ungodly woman I ever met. I heard her husband plead with her, “Have the children baptized, sweetheart, and bring them up in the church.” and before the visits were over, she did give in finally. I helped her arranged for the baptism of their two boys at a neighboring church.

I was present the day the defendants were assembled in the courtroom and, one by one, given their sentences. As far as I could see, none flinched when he heard his fate.

Franz von Papen, Hjalmar Schacht and Hans Fritzsche were declared free men. Rudolf Hess, Walter Funk and Erich Raeder received life imprisonment; Baldur von Schirach and Albert Speer, twenty years; Baron von Neurath, fifteen; and Admiral Doenitz, ten. The eleven others were sentenced to death by hanging.

For reasons of security, the defendants were no longer permitted to attend chapel. Those not sentenced to die were moved to the second tier of cells. The eleven doomed men were given one more chance to see their wives. As Goering was about to part with his wife for the last time, he asked what little Edda had said about what was happening.

Emmy answered, “She says she wants to meet you in heaven.”

He stood up and turned away. For the first time I saw tears in his eyes. When I went later to his cell, he said simply, all the bombast gone out of him, “I died when I left my wife upstairs.”

We chaplains now worked feverishly with the men. Some asked us to stop in four and five times a day. Sauckel was so unnerved that I feared he would crack up. He would pray aloud, invariably ending our sessions with “God be merciful to me, a sinner.” Keitel concentrated on Scripture which spoke of redemption through Christ. Von Ribbentrop read his Bible most of the day. These three took communion with me in their cells. On October fifteenth, the last day, the tension was terrific. We went from cell to cell, again and again, staying a few minutes with each man.

That evening, around 8:30 I had a long session with Goering–during which he made sport of the story of creation, ridiculed divine inspiration of the Scriptures and made outright denial of certain Christian fundamentals. Then suddenly, to my astonishment, he asked, “How do you celebrate the Lord’s Supper?”

“You claim membership in the church. You must be familiar with its sacraments,” I reminded him. I reviewed the doctrine, emphasizing that only the fully penitent should partake.

“I have never been refused communion by a German pastor.”

“I cannot with a clear conscience commune you, because you deny the very Christ who instituted the sacrament.”

His attitude was, “Just in case there is anything to this business of yours.”

“You remember what your little daughter said?”

“Yes, she believes in your Savior,” he said slowly. “I’ll–take my chances.”

And so I left him–for the last time. I was in the guard room about 10:30, when a guard rushed in to summon me. “Goering’s having some kind of spell!” he cried. I hurried to the cell with the guard, who stood at the door as I bent over the big man lying on his back on the cot. ONe hand was on the floor, his eyes were rolling and there was a gurgling sound in his throat. On his chest lay a tiny capsule.

“Get the doctor!” I told the guard. “This man’s dying!”

Desperately, not knowing what else to do, I leaned close to the unconscious man and spoke Scripture in his ear. The prison doctor, a German, came quickly. He called for the other medics. An American doctor rushed in. Then the officer of the guard. Suddenly the room was full.

The Reichsmarshal was dead. Self-execution by potassium cyanide was his crowning achievement. Intense excitement prevailed throughout the prison. Colonel Andrus asked me to tell the other victims what had happened, and to warn them they would be closely watched. But most of them thought what Goering had done was on the craven side–they had had to listen to him brag for over a year about how brave he would be to the end.

At midnight, the indictments and the sentences were again read to the condemned. the last meal was offered. Only a few ate. Von Ribbentrop was the first to go. Before he left his cell, I prayed with him and heard him say that he put all his trust in Christ. Then the signal was given for the start down the corridor. Colonel Andrus led. Father O’Connor and I followed, sided by side. Behind us came von Ribbentrop, between two guards. We walked out of the prison door, through the courtyard and into the execution chamber.

A guard tied the doomed man’s hands. Then he was marched to the foot of the first of three gallows and told to give his name. He was taken up thirteen steps to the trap door. There he stood face to face with the impassive spectators assembled as official witnesses. The guard then tied his legs. An American officer asked if he had a last word to say. I do not recall all of von Ribbentrop’s final statement, but it ended with “God have mercy on my soul.” Then he turned to me and said–and my heart still warms when I think of it–“I’ll see you again.”

I spoke a brief prayer. Then the big black hood was pulled over his face, the knot with thirteen coils adjusted behind his head–and he dropped through the trap door.

The second was Wilhelm Keitel. Our period of prayer in his cell was drenched with his tears. At the gallows we repeated together a prayer we had both learned from our mothers. He then said, “I thank you, and those who sent you, with all my heart.”

Chaplain O’Connor accompanied the next man to the trap door while I stood nearby.

When the signal was given for Fritz Sauckel, my heart actually skipped a beat. He had been so unnerved during the final twenty-four hours that I wondered if he would bear up. When he stood on the trap door and spoke of his wife and many children, I was so jolted that I thought for a moment I could not go on. I, too, was becoming unnerved by that time.

“Julius Streicher (standing), editor of the anti-Jewish newspaper, Der Sturmer, was unrepentant to the end. When he walked up the steps to the gallows, he defiantly shouted, ‘Heil Hitler!’ “

The last of my group was Alfred Rosenberg, who had consistently refused all spiritual assistance. I asked if I might say a prayer for him. He smiled and said, “No, thank you.” Julius Streicher was the last to die. He at first refused to give his name. And as he walked up the steps he did “Heil Hitler.”

Press reports to the contrary, Streicher was the only man to cry out after the hood descended. As he went through the trap door, he spoke his wife’s name.

It was a little after three o’clock in the morning, October 16, 1946.

Thus died eleven men of intelligence and ability who, differently influenced, could have been, I am convinced, a blessing to the world instead of a curse. For all my own blunderings and failures with them, I ask forgiveness.

As they died, so will certain men of the Kremlin someday face eternity. For evil is always its own destruction. If, by reason of our own weaknesses, they could take our country first, there would be no chaplains standing by at the gallows they would man.

Let Americans remember that the gross hates and cruelties which climaxed in the careers of the Nazi leaders had their inception in the petty hates, prejudices and compromises of millions of little men and women–some of them quite pious too.

.

.

*Text and photos from Philadelphia: The Saturday Evening Post, September 1, 1951, pages 17-19, 57-58, (author’s collection).

.

.