The Chapel of St. Mark at Fort Marion

Fort Marion, now a U.S. National Park site, is the oldest existing masonry fortress in the United States. It sits at the harbor entrance at St. Augustine in Florida. The Chapel of St. Mark, which was part of the original fort built by the Spanish, is an excellent representation of Spanish-Catholic commitment to providing a worship space for their garrisoned soldiers.

The Spanish arrived at the present site of Fort Marion in August if 1565 and established the colony of San Agustín in September. Having barely survived attacks from the French and British with their hastily-built forts, on 2 October 1672, the Spanish broke ground on what would be Castillo de San Marcos but it would take 84 years to complete.

In 1740, enough of the fort was completed to offer safety to the besieged garrison and citizens of San Agustín when James Edward Ogelthorpe, from the British colony of Georgia, attempted to conquer it. The fort proved to be impregnable as canon fire from Ogelthorpe’s guns did little damage. During the 27-day siege, “the garrison chapel was the scene of daily Masses, and occasionally marriages and christenings…”1

In 1740, enough of the fort was completed to offer safety to the besieged garrison and citizens of San Agustín when James Edward Ogelthorpe, from the British colony of Georgia, attempted to conquer it. The fort proved to be impregnable as canon fire from Ogelthorpe’s guns did little damage. During the 27-day siege, “the garrison chapel was the scene of daily Masses, and occasionally marriages and christenings…”1

In 1762, Havana, Cuba was captured by the British and traded back to the Spanish for all of its Florida territory, to include Castillo de San Marcos. Early in 1764, as the Spanish left San Agustín the British moved in and renamed the town St. Augustine, and called the fort Castle St. Mark.

During the American Revolution, St. Augustine became the headquarters for the British southern campaign and the fort held American prisoners, some signers of the Declaration of Independence. In the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which ended the Revolutionary War, Spain ceded Jamaica to the British, and in return received Florida back.

During the War of 1812, American troops approached the gates of Castillo de San Marcos without military opposition but were recalled before being able to attempt its capture. However, on 10 July 1821, as Spain’s power and influence decreased, the United States took control of the fort from the Spanish and four years later renamed it Fort Marion, after General Francis Marion from South Carolina, famous for his Revolutionary War successes as the “Swamp Fox.” It was later abandoned so in 1861 when Confederate volunteers marched on it, it was defended only by a caretaker with the keys to the fort, who reluctantly turned them over to the Confederates who held the fort for only 14 months until 8 March 1862 when a Federal naval detachment approached St. Augustine to discover the fort had been abandoned the night before.

During the Spanish-American War (1898-1899), Fort Marion housed court-martialed American Soldiers, who were the last residents of the fort as a military garrison. In 1924, Fort Marion (along with Fort Matanzas) was declared a National Monument and continued under War Department control until 1933 when it was transferred for care to the National Park Service.

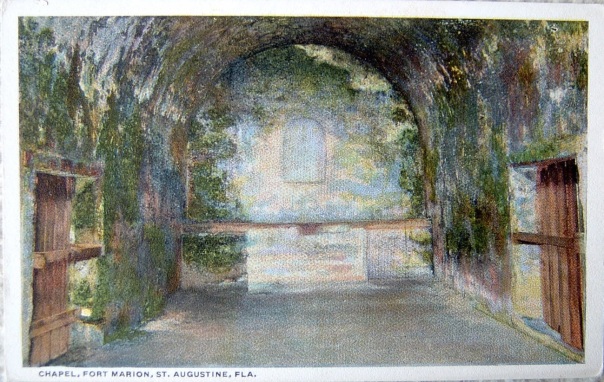

The Chapel of St. Mark, dedicated by the Spanish in 1756, is “At the north side of the court, directly opposite the sallyport … The entrance to this room was very ornamental. This work, which had become nearly obliterated by the action of the elements, has recently been reconstructed by the War Department, great care being taken in following the original plans, which were obtained from the Spanish Government. Entering, we see on each side the niches for holy water; just beyond, on the right, pieces of cedar imbedded in the masonry mark the place where the confessional was fastened to the wall. At the rear is a raised stone platform for the altar, and above the altar a large niche where stood the patron saint, Saint Augustine. Looking up, we see near the spring of the arch the ends of the old timbers which supported the platform for the choir. Directly overhead, near the middle of the room, is a square hole from which hung an immense wooden cross called the rood. On either side of the chapel are doorways through the iron bars of which the prisoners could hear mass before being executed. The bars were necessary, as if a prisoner gained access to a chapel and knelt at the altar, he could claim the right of sanctuary.”2

.

Entrance to Chapel of St. Mark before restoration.

Entrance to the Chapel of St. Mark

Early photo of the front of the Chapel of St. Mark

“Chapel, Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Fla. Showing niche for the patron saint, St. Augustine, and the altar. Also doors at sides through bars of which prisoners were allowed to hear mass before being executed. The brightest and most patriotic Spanish clergy have celebrated mass in this room” (from back of 1900s postcard).

Holy Water Fountain on the west wall of the chapel (photo by George A. Grant, ca 1947)

Modern photo of the Holy Water Font.

Modern photo of the Chapel of St. Marks. On the altar are pictures of digital recreations of what the chapel may have originally looked like.

“Ledger Art” by Plains Indians who were incarcerated there 1875-1878. “The Chapel: Sunday Evening Service.”

.

.

Sources:

1 NPS Guidebook for Fort Marion and Fort Matanzas, 1940, found online here.

2 Exerpted from “St. Augustine Under Three Flags: Tourist Guide and History,” W. J. Harris Company, 1918, pp. 17-21, found online here.

http://www.nps.gov/casa/index.htm

https://classyhdr.wordpress.com/tag/military-forts/

http://weaponsman.com/?p=26880