[British] Army Chaplains at the Front

![[British] Army Chaplains at the Front [British] Army Chaplains at the Front](https://thechaplainkit.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/boer-war-rev-wj-adams.jpg?w=105)

This article is from the 28 April 1900 issue of the British publication, the Sphere, written by Rev. E. F. Hardy:

Mr. Hardy, who has just written a capital book called Mr. Thomas Atkins, is a graduate of Trinity College, Dublin, where he had a distinguished career. He joined the army in 1877, has served in many parts of the world, and is now a chaplain of the first class, ranking as a colonel. He is at present stationed at Dublin, where he delivered the Donnellan lectures at the Trinity College Chapel last year. He made his first hit as a writer with How to be Happy Though Married, published in 1884.

The pen is anything but mighty with me, but it is mightier that the sword. I am not a man, not even a clergyman, of war, but when chaplain at Netley Hospital I saw only too much of the results of war, and perhaps I may be able from what I do know of our work on the field to interest Spherical readers with a short account of campaigning chaplains.

During the Egyptian war of 1882 I went one day into a military hospital and found that almost all the occupants of one ward were to have a wounded arm or leg amputated, or to undergo a much worse operation the following day. It was a glimpse of the horrors that are attached even to a little war.

We chaplains see war literally in cold blood. We have not the wild pulsation of the fight to sustain us. Our place is with the wounded on the field after the battle and in the hospitals and there is no romance of war there.

Some chaplains consider it their duty to be in the thick of the fight. One of these, Rev. J. Robertson, before the Boers had done killing our been, and before Mr. Atkins had stopped firing at those whom he could not see, used to ride over to the enemy and ask permission for the wounded and dead to be carried away. “I knew that they would not harm me,” he said, “because they could see by my going up to them that I was either a minister or a madman.” “You’ll become a Boer yet,” said a general officer to him, “if you go over to them after each fight.” “No fear of that,” was the reply, “but I’m bound to say that they have been very courteous and kind to me.”

This was a Presbyterian chaplain, but a Roman Catholic one, Rev. R. F. Collins, who spoke German well and went on the same errand, also discovered that the Boers, like another personage, are not so black as they are sometimes painted.

At Belmont the Grenadiers were scaling the steep kopje, and men were falling fast. From one wounded soldier to another went Church of England Chaplain Rev. F. A. Hill, lifting a head here, giving water there, commending a departing soul to the God who gave it. “Go back, Padre, go back!” said an officer. “No,” he replied, “I’m in my right place here.”

In a war like the one in South Africa, where surprises and Boer traps are so frequent, and, of course, in campaigns against Fuzzy Wuzzy people who do not understand the Geneva Red Cross, the peaceful nature of a chaplain’s calling, or any of the courtesies, so to say, of civilised campaigning–in cases like these chaplains are, as the hymn they so frequently announce says, “Oft in danger, oft in woe.” You never know where you are in these days of long-range weapons. You may be in a battle for hours without being aware of it, and his reverence the chaplain may be sniped at, though two thousand yards away, from behind a rock by someone who has no respect for the “cloth,” even if he could distinguish it.

There is much roughing for everyone on a campaign, but a chaplain is particularly uncomfortable. Unlike other officers, he does not belong to any special regiment or corps, the advantages of which he could have shared. Sometimes, however, there is an exception to this rule, as when a Presbyterian chaplain is attached to a Scotch regiment. This gives him a feeling of security. Wandering too far from camp one day, during an Afghan campaign, a Presbyterian chaplain was set upon by the enemy. He took to his heels and ran back shouting, “92nd Highlanders, help! These fellows have been impertinent to me!”

About twenty-five commissioned Church of England chaplains, and some paid and unpaid acting ones, eight Roman Catholic, six Presbyterian commissioned chaplains, and four Wesleyan acting ones, were sent to the present war. Local clergy were also employed as acting chaplains. The number of chaplains of each denomination is regulated by the number of men of that persuasion that are at the front, for in the army there is perfect religious equality. Commissioned chaplains, whether Church of England, Roman Catholic, or Presbyterian, are divided into four classes, and rank as colonel, lieutenant-colonel, major, or captain, according to the class they are in.

Do we agree together like birds in their little nests? Yes, better than do civilian ministers of the Gospel of Peace. At some home stations we use the same building for worship, at different hours, of course, and necessarily so during war, for then it is God’s own cathedral under the blue sky, about which there can be no exclusiveness. If indeed odium theologicum and narrow-minded jealousy were indulged in by those who have different methods of sky-piloting, it could scarcely continue amidst the awful sights and smells with which “grim-visaged” war makes campaigners familiar. The self-forgetfulness of the “gallant private” would also rebuke us if we thought much of our individual fads, fancies and fashions of religion. A piece of shell had carried away the left eye of a soldier; there was a hideous cavity in his cheek through which the root of his tongue could be seen. Of course he could not speak. So when brought into hospital he made signs for something with which to write. Getting pencil and paper he asked for nothing for himself, and made no complaint, but simply put down, “Did we win?” Active service cures the bigotry which inaction may have produced. It makes us think, not of ourselves, but of the common cause of goodness and practical religion, and we ask are we winning–we who represent Christ of the many-coloured but unparted robe amidst the death and devilry around us.

The duty of a chaplain on the field is to make himself generally useful. After the battle of Belmont a chaplain, a friend of mine, wrote that from nine o’clock in the morning until six o’clock in the evening he was busy doing what he could for the wounded, and after this for two hours engaged burying the dead. “The one thought of the wounded was for the other wounded near them. Fortunately I picked up tow water-bottles nearly full, and though the water in one was very hot it was most thankfully received by the men, and what was left by the officers.”

“Tommy,” says my friend, “is a different being in war-time. I hear no bad language, and no grousing. On their way up here civilians pressed drink upon them, but they would not take it.” After parade-service some men came to another chaplain at the front, from whom I heard, and asked him to have a voluntary service in the evening, and also to have a special communion service, as some of them were to be sent away. “So different this from at home when, as you know, we have to ask them to attend our ministrations.”

On active service church parade is rendered particularly impressive by the consideration that before next Sunday’s service many present may have “gone under,” be “knocked out of mess,” become a “fatal casualty,” or whatever we call it. Drawn up row behind row in three sides of a square are men who within the week had been face to face with death, and were going to face him again in a few hours. Here, surely, is a preacher’s opportunity.

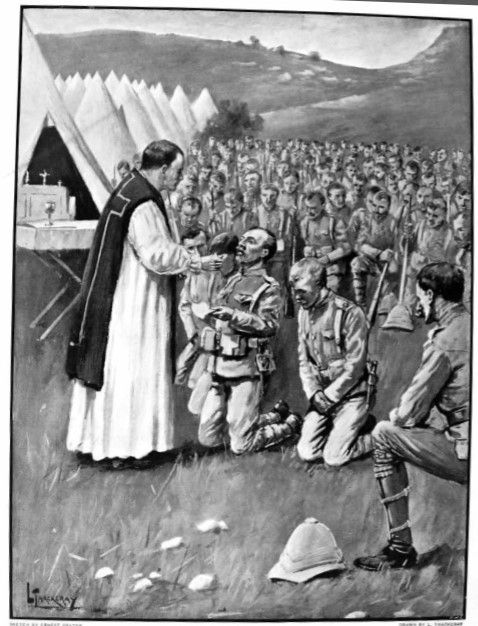

The striking picture on the opposite page [(below)] gives some idea of the impressiveness of a religious service in camp, conducted by Father Matthews. –Editor.

“FATHER MATTHEWS ADMINISTERING THE SACRAMENT. The Rev. Lewis Joseph Matthews, who ranks as a major, was captured at Nicholson’s Nek on October 30, but was liberated a little later. He went through all of the engagements with Buller up to the relief of Ladysmith…(drawn by L. Thackeray).”

.

.

Here are the two pages from which the above article was drawn:

.

.

.